- Home

- Bob Rosenthal

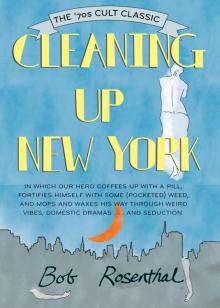

Cleaning Up New York

Cleaning Up New York Read online

Copyright © 1976 Bob Rosenthal

Cover © 1976 Rochelle Kraut

Photograph © 1976 Maryann Gerarduzzi

Design Katy Homans

Cover and illustration © Rochelle Kraut

Cover type, color, production Evan Johnston

Originally published in an edition of 750 in 1976 by Angel Hair Books, supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rosenthal, Bob, 1950- author.

Title: Cleaning up New York / by Bob Rosenthal.

Description: New York : Little Bookroom, [2016] | ?1976 | Originally published: Lenox, Mass. : Angel Hair Books, 1976. | Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015038920 (print) | LCCN 2015038651 (ebook) | ISBN 9781590179901 (epub) | ISBN 9781936941131 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Rosenthal, Bob, 1950- | Poets, American—20th century—Biography. | Cleaning personnel–New York (State)—New York– Biography. | Cleaning. | New York (N.Y.)–Social life and customs– 20th century. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | HOUSE & HOME / Cleaning & Caretaking.

Classification: LCC PS3568.O8367 (print) | LCC PS3568.O8367 Z46 2016 (ebook) | DDC 818/.5403–dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015038920

ISBN 978-1-93694-113-1

eBook ISBN: 978-1-59017-990-1

All rights reserved, which includes the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof, including photographs, in any form whatsoever, without written permission of the publisher.

THE LITTLE BOOKROOM

435 Hudson Street, Room 300

New York NY 10014

www.littlebookroom.com

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

CHAPTER 1

The Nature of Cleaning

CHAPTER 2

How Things Get Dirty

CHAPTER 3

Organization of Tasks

CHAPTER 4

Dusting and Furniture

CHAPTER 5

Floors and Walls

CHAPTER 6

The Bathroom

CHAPTER 7

The Kitchen

CHAPTER 8

Special Jobs

CHAPTER 9

Hints

CHAPTER 10

The Clean House

$60. I needed $60 in three weeks’ time. I was out of a job so the idea of doing temporary work just popped into my head. I called a friend who had once done cleaning jobs and he told me to call up Everything for Living Space. He said I’d have to lay out $15 in order to register with the agency. Shelley and I have only been eating rice and beans; I felt I held our future in my hands as I grabbed the checkbook and took the subway up to Broadway and 72nd Street. My trepidation doubled as I stepped into the noisy, broad vacuum created by the large gray buildings that outline Needle Park. My mind thumbed back over pages of Naked Lunch that settled on this location with a green fog. My ears picked up the soundtrack to the movie Panic in Needle Park, which must have been just a microphone hung outside one of these dirty windows. I found the address on 72nd Street and entered the lobby sure that I was about to be jumped as I punched the big, black, knobby button on the elevator. Released into a thin, filthy green, corridor, I pumped my feet up to a frosted-glass door lettered EVERYTHING FOR LIVING SPACE.

Barbara, a flamboyant redhead with a brassy, theatrical voice, became the focus of my attention as the door shut behind me. Her evocative manner of speaking put me at ease and I began to see cleaning as a possible and perhaps glamorous thing to do. Barbara would get me cleaning jobs at $3.50 an hour with a four-hour minimum, after I provided her with two references and the $15 deposit. I gave my former boss and the poet Ron Padgett as references and put down the money. Barbara said she would call me as soon as I was cleared. I walked out, back into the gray fumes of that day. Out of work, nowhere special to go, I shuffled over to Central Park West and started ambling up past noble apartment buildings, awnings, and yawning doormen. I spotted a gold trinket on the sidewalk, picked it up, and held before my eyes a small brass button. I asked a nearby doorman dressed in a green uniform if the button belonged to him. He couldn’t speak English, but he understood the question and answered it with a negative. I told him I must have been promoted and he gave me a congratulatory smile. Walking up Central Park West, my stride gained and I straightened up. Passing soldiers of courtesy, imperious apartments overlooking the green domains of the park, I felt my bootstraps pulling; I knew I was on the road to success. I walked into the Museum of Natural History and proffered a quarter for which I received another button. A dinosaur was drawn on it and the word “contributor” was written below the extinct animal.

Success came the next day in the form of a command from Barbara via the telephone: Go to Interior Design showroom on Lexington Avenue, 59th Street. The first hours passed easily, working with a cheerful middle-aged Jewish wife. I had to move a few objects around the showroom and rehang pottery and macramé junk wall-hangings. Later in the afternoon, her husband, the boss, came in. He was the kind of guy who talks fast, is pushy, and can’t ever give a direct order. I found myself doing the endless bits and pieces of his undone chores. Each task was a little more tedious and backbreaking than the last. My coordination lessened as the difficulties mounted. I uncrated furniture, changed light bulbs, and tacked up little metal tiles using thumbtacks that would not stick in the wall; and I cleaned out a closet left over from the Fibber McGee and Molly radio show. I consoled myself with the fact that I was getting in plenty of hours. I worked into the evening with no food or rest. I was just about to faint when the miracle occurred. I got paid and set free. I worked and the result was over $20, green and needed, in my pocket. I bought a hamburger and an ale and brought them home. Shelley lifted her tired head off the kitchen table as I came in the door. How bizarre the sizzle of the meat seemed and how delicious seemed the perspiring, green Ballantine Ale! Shelley and I ate the hamburger and drank the ale and said, “Pretty good!”

The next time I met Ron Padgett, the poet I had used for a reference, he told me of a phone call from a strange lady asking if I was a good housecleaner. At first, Ron thought it was a joke, but when he realized I needed a character reference, he informed Barbara that I was an exceedingly clean person and always brushed my teeth. I made the $60 I needed that month plus enough to register again with the agency. Without thinking twice, I became a fresh recruit in the ranks of the cleaningmen.

CHAPTER 1

The Nature of Cleaning

“Clean” is an Anglo-Saxon word, which comes into modern pronunciation with little alteration; it means to wash and to make bright. Dirt collects at the intersection between a solid surface and air. Some of the dirt is sitting on top of dirt and is really more in the air than on the counter or floor. This dirt is cleared away and air fills the space just vacated. However, there still remains the dirt that is in direct interaction with the solid surface. This surface must be worked on in such a way as to make it bright. The duality of surface and air is paralleled by a similar duality in cleaning, that of clearing and shining.

In regard to the human body, cleaning is movement or the expenditure of energy. The basic duality of cleaning extends to the mind and the body of the person cleaning. The body does the clearing and the mind does the shining. The mind conceives of cleaning and of cleanliness as a virtue. Cleaning is its own reward for those who don’t resent a collaboration with bodily efforts. And for people who like to hire me, a clean house is the

ir reward. The mind must be really shining in order to put the body through what is a vigorous routine.

Cleaning involves the body from its extremities to its center. One is often standing on tiptoes or crouching on them. Fingers are subjected to the almost constant exercise of rubbing. The legs are stretched in deep knee bends and the muscles of the wrist and forearm start to bulge from hard use. The extending of arms works the shoulder muscles and bending over at the waist stretches the dorsal muscles of the legs. The stomach and lower back muscles stretch and contract to buoy up the torso as it leans over, straightens up, and leans over again. Between all of these exercises there is a coordination that turns cleaning into a slow ballet. When the body has learned how to work the cleaning process without conscious instructions, the mind can go slightly blank, just giving off a little shine. The body will go on with grace and unconscious artistry.

The mind should be organized to know the proper order in which to proceed through a series of tasks. Discovering that you are throwing dirt onto a surface you had cleaned the minute before creates mental fatigue and your motions become directionless. Direction is a natural pursuant to coordination; when you know the number of steps it takes to get some place, you know where you are at any given point, you know what comes next, you know you will reach your destination. When you clean a space regularly, you learn the number of steps needed to clean it and when you are done, you straighten up and admire the path of hard work that brought you here.

Cleaning is slow and ritualistic; it is about everything getting washed and purified, about seeing each thing in its natural spirit. When you clean, you mingle with the released spirits of objects, such as sinks, chairs, windows, and floors. When you are done cleaning each object within a certain space, then the room is clean. To the body at work the idea of a “clean room” is abstract reality. It is something larger than what you can actually touch, yet it is also contained within you. Your own sense of yourself is larger than what your motions define at the moment of cleaning. The ritual of cleaning puts you in touch with yourself as the essence of each thing you clean is revealed to you. By soaring along with the free spirit of things, you meet parts of yourself on the frontier between your own spirit and all non-worldly spirits. The slowness and evenness of cleaning prevents you from being startled or blinded in your thoughts. The spirit of cleaning is a state of trance and fascination.

In my first month with the agency, jobs fall into my lap at unexpected times. The strange hours and locations of these jobs make each one singular in my mind except for the number of them. The mystery and fear of “When will the phone ring?” and “Where do I go?” makes going to work like going on a caper. The phone is ringing. Barbara’s obstreperous voice is like a backstage knock: “Are you ready?” and soon I’m gone.

I wash windows and wax the floors in a West End apartment newly occupied by two civil liberties lawyers soon to be married. I fatigue myself buffing a paste-waxed floor by hand and I take enough dope for a couple of joints from their modest supply of marijuana. I get called out to Bayside, Queens. An hour and a half on subways and a bus leads me to fresh air, grass and trees, and incredibly long rows of bungalows with six-digit house numbers. In my appointed house, I learn the use of acrylic floor wax. I have to clean and wax the floor in the large recreation-basement room. Some of the brown-and-white asphalt tiles are bent to right angles with the floor. The atmosphere is dark and dank; the plastic wood-paneled walls hold large oil canvases, each picturing a particular fat naked man. He is the man who let me in the door; his wife must be the artist. The acrylic fluid splashes over my hands and dries into thin sheets of shine. I have to learn how to distance myself from this cosmetic cleaning product because it is dangerous to the user. Inhaling acrylic floor wax fumes clogs the lungs and prevents breathing for a few moments. Upstairs the artist gives me a tuna fish sandwich; I tell her that her paintings remind me of Alex Katz, because of their big flat colors. She hates Alex Katz, wowee! I go to the medicine chest and take some valium. It keeps me from worrying about if I will ever get done. I still have the downstairs and the upstairs left to do. As I vacuum the living room, she drinks a beer and watches a soap opera on TV. She lifts her feet and I vacuum under them, then she offers me a beer. A long day’s pay plus tip and carfare convinces me it was a good performance. “I pulled this caper off!”

A businessman rents and sublets a studio in the East Fifties. The last person had left the place totally disheveled. The businessman tells me to throw out all the junk lying around or take it for myself. He thinks it is going to be a near impossible job and promises me a $10 tip. He goes on to work and I start to reconstitute the apartment. In about four hours, I have everything clean and straight and I have a BOAC bag filled with select items for me to take home. I have a new plant sprayer, new plant food, new earth, new Band-Aids, new shampoo, new blue jeans, new tools, and a little new grass. I meet my boss in the lobby of his office building and hide my bag of goods behind a desk in case he should reconsider that tip. He does think hard about the tip because I am faster than he thought possible; of course, he can’t see the finished product. I give him a look full of expectation; he shoots back a pained expression and hands me the tip. I tell him that he will love it and jump down into the subway rich with expensive household items plus hard cash.

These capers teach me quick perceptions as to where dirt is and isn’t and how to organize a cleaning plan. When I go into a strange apartment, the standard procedure is for the employer to explain what is to be done and where the materials are kept. I learn how to begin. Beginning promptly builds trust in employers and relaxes them. Once I have begun, I find that the plan formulates itself from common sense and natural body movements. These perceptions coupled with insights into people develop in me a talent for cleaning a place the way the employer wants it cleaned. I find that I become a slave to my own intuition of another person’s will. The talent for knowing how to clean differently for different people makes me feel skilled. Most people are frank with their appreciation for my work except those people who consider themselves among the wealthy. I discover for myself that the one way rich people stay rich is by not appreciating true skill in common workmen. I do a good job in an East Sixties penthouse and the lady asks me if I know how to make a bed. I say, “I guess I know, sure I can make your bed.” Her bed has a complicated system of undersheets and oversheets and a bedspread, all which have to be turned in precise ways. I do a passable job though not a lady’s maid’s job with the bedding and she complains about it just before she pays me. I realized later that she complained just so she wouldn’t have to tip me.

One day Barbara calls me up with what she calls a “goody.” A Mrs. Cunningham in the Village needs a cleaner plus a little care in the home for her husband who had recently suffered a stroke. “A real sweet gal,” Barbara describes her. On a bright, sunny morning, I walk through Washington Square Park with five Frisbees buzzing around my ears. Mrs. Cunningham lives just off Sixth Avenue below the Waverly Theater. The door to the building has brass plates shining my golden complexion before my eyes. I buzz up and my reflection swings away into the most organized apartment I’ve ever seen. The floors are natural wood stained dark brown with a few handcrafted throw rugs carefully placed. There is built-in wood cabinetry that cleverly holds books, a hi-fi, liquor closet, and desk. A folding table sits squarely at attention flanked by two matching wood chairs along the side wall. Next to the table is a small working fireplace with a marble slab for a hearth. Across from the fireplace is a soft brown upholstered couch with a round wooden coffee table in front of it. Near the front windows is a dull gold upholstered chair with three end tables that fit under one other. On the walls are large canvases of geometric forms precisely colored. The paintings are so subtle that it is hard to see how they are good. The kitchen is in the front with a window over the street. It is small with built-in cabinets, a big sink, and a tile floor with a design of dark brown tiles that smacks of the paintings. The bathroom is

brown with a brown carpet. The bedroom is in the back, brown wood bookcases built around the windows and a cork floor. The big king-size bed has two built-in lights on the wall above the headboard, one over each pillow, and separate switches. Here is my dream of a perfect marriage realized!

Mrs. Cunningham is middle-aged, wears red lipstick and a short haircut. She is slim and petite and gracious with a strong sense of justice that animates all her qualities. She introduces me to her husband, Ben. Ben has had a couple of major strokes leaving him able to take care of himself in simple matters but unable to paint anymore. Ben is the painter of the canvases on the walls. He is in his mid-sixties, white-haired with a big white moustache. He is tall and gaunt with a confused look in his eyes that sometimes focus into a clear sparkle. Mrs. Cunningham has been housebound since Ben’s illness and plans to use me in order to allow herself to step out for a few hours. She leaves me a detailed list of everything to be cleaned in each room and the proper product to use for each task. I make Mrs. Cunningham comfortable in her mind that I am not uptight about keeping an eye on Ben. I am more worried about the cleaning. When I can see a room as well as I can see the living room, I know that it is already clean. For me, learning to clean the clean will be the challenge.

The Cunninghams own the building and one of my duties is to sweep the staircase and polish up those brass plates. Above the apartment, separate only as a separate reality, is Ben’s studio. Here laxity of order and individual quirks rule; here is the TV. Giant paintings are stored in racks and all around are tools, artist’s supplies, toys, and a bugle. The attic walls slant up into a skylight and the light comes down around me, putting my roots into Greenwich Village. I feel the sense of times before me and the dignity of an older way.

Mrs. Cunningham’s first name is Patsy—I find out when Ben calls me Patsy—Patsy likes the way I clean and eagerly engages me again and with handsome terms. I am to receive four hours at the cleaning rate of $3.50/hr. and $3.00/hr. for any time over four hours when I would sit with Ben. During my second day’s work for the Cunninghams, someone rings the doorbell and I buzz the person into the building. A frumpy man is walking up the stairs. I open the door and the man just walks in. Ben seems to recognize him. They both sit down on the couch in very similar distracted manners and I sit in the other chair intent on what would ensue. After the visitor utters a few words, it is apparent that he is crazy and in fact his conversation is primarily concerned with his last five years in a mental hospital. I gather that the man had once been Ben’s student. Both he and Ben speak their own way for a while, neither one comprehending the changes in the other. I suggest to Ben that he may be tired; he assents with a clear look, knowing it is an excuse. I usher the fellow out and get his name in order to report the story to Patsy. She is pleased with the way I handled the situation and her confidence in me is boosted. Soon I am working at the Cunninghams’ four times a week.

Cleaning Up New York

Cleaning Up New York