- Home

- Bob Rosenthal

Cleaning Up New York Page 2

Cleaning Up New York Read online

Page 2

With this much work, I no longer need the agency. I tell Barbara of my good luck and she heartily congratulates me. Patsy always leaves the house when I am working, so soon I feel in control as cleaner and sitter. I could give Ben a tranquilizer if I want, though I don’t unless he gets terribly frustrated and irritated. Ben sits all afternoon smoking BETWEEN THE ACTS little cigars. He has a problem striking the match; lighting his cigars becomes a gracious part of my cleaning movements. Swinging by with the vacuum, throwing a courteous arm and hand with lit match, pulling the vacuum back with the other hand as Ben lights up. Ben and I never converse but he is up to pulling a good trick on me. I am vacuuming the living room and the machine is plugged into a socket located in the washroom. Suddenly the machine goes dead and I turn to see Ben with the plug holding it under the open faucet. My first thought is, “Aw my God, he’s gonna plug it back in—wet!” I run up to Ben and calmly ask him what he is going to do. “I mean, Ben, it’s great and everything but I’m just curious to know why you did it.” He looks deep into me and his eyes become clear as pinpoints and he says, “To confuse you.” That’s the right answer and I fall in love.

Being the housekeeper at the Cunninghams’ allows me to play around with the cleaning a bit. There are certain things I do every week, but there are other things that only need doing every so often at my discretion. Occasionally I shampoo the rugs, or wax the floor, or concentrate on all enamel surfaces. My initial trepidations about the cleaning soon dissolved in this freer state of cleanliness. This is the model house to learn housekeeping in because it is so well organized that there is no clutter or interference from human frivolities. I learn how to arrange little surprises for Patsy to find a few days after I’ve cleaned. I clean out-of-the-way areas such as a shelf behind the shower curtain or a row of books. Sometimes I imagine the things I clean may not be discovered for weeks or months. I work steadily at the Cunninghams’ until Shelley and I plan to leave town for the summer. I am saddened to leave such a gracious home, especially one where there are people I love; Patsy and I arrange to contact each other about work in the fall.

CHAPTER 2

How Things Get Dirty

In New York City, we really live like worms. There is dirt above, below, and on all sides of us. The air is a constant fine mist of dust and soot. Filth is creeping up from every basement. Cockroaches and insects are constantly chewing things into little piles of dirt. Pigeons! Dogs! Dirt is puffing between floorboards and under walls and down from ceiling cracks. Corrosive chemicals in the air eat away the faces of statues and crumble the bricks about us. The subway blasts subterranean filth up through air grates. People throw their dirt everywhere. There is garbage and cigarette and cigar ash in the streets; rooftops are often junk heaps. Now back into our wormhole: the apartment. We tread dirt inside on the soles of our shoes. Our clothes literally shake with dust. Our hair is a broom that sweeps in the city atmosphere. We come in like bombshells.

Dirt distributes itself by the motion of rise and fall. Dirt enters an area with some impetus. Air coming under windows sends dust floating around the ceiling, which slowly sifts its way to the floor. This dust will settle on any crevice no matter the size. This means bumps in the paint on your walls have tiny motes of dust just hanging around. (Let me toss an aside into the dust storm. This all sounds neurotic but it isn’t. It is just the heightened perception created by the direct contact of my labors. I don’t dislike dirt. Far from it, I feel very comfortable working with dirt.) Dirt is heavier than air so it settles down on every surface from the ceiling to the floor. The rim of your lampshade is doing a good business right now. As you shuffle across the floor, you are kicking up particles that jump up and fall down a few feet away. Cooking often sends a film of grease through the air that sticks to anything it can touch. As you soak in the bathtub, dirt floats along the surface of the water and spreads over the walls of the tub as it is drained. The toilet bowl is the scene of miscalculations that send dirt down the wrong side of the bowl! Your ablutions spatter the walls and get the tiles dirty. Water is one of nature’s best solvents; if you splash the floor while doing the dishes, then the water will strip the dirt off the bottoms of your feet.

Pets are as bad as city environment or people when it comes to getting things dirty. Dogs and cats shed their coats everywhere they go. They shred up pieces of paper, knock over flowerpots. Cats kick and scratch at their cat litter until it is littered all over the floor. No dog is above having accidents. Dogs run along the walls blackening them and furiously beat dust up into the air current with their tails. Birds throw shelled birdseed out of their cages and if you let them fly free—well! All pets use their unnaturally confining space to its utmost.

Getting dirty is a process of natural inertia. Dirt moves by force and then rests. Cleaning has no natural inertia unless you telescope your thinking into geologic time and everything gets washed into the sea. The washing we do is toward a more limited end. Dirt will always win in the end.

Shelley and I come home to New York City, and the recurring need to make money prompts me to send Barbara $15. Within seventy-two hours, Barbara thanks me with Cherry Malard. Cherry sounds sweet as she tells me that repairs have been made in the washroom and the kitchen needs to be mopped. The building stands nicely in the sun in the East Eighties, only a door and a half off First Avenue. The apartment doesn’t answer the bell, so I sit on a red bench in front of the building. Brightly around the corner comes a pretty black-haired girl walking a large dog. She walks up to Cherry’s door and we recognize each other. Cherry leads me into the hallway of her first-floor apartment. It is a tall, cramped space with white hexagonal floor tiles as often found in washrooms. I follow Cherry down the hall and glance into the bathroom before we empty into the kitchen. Cherry shows me the work and the equipment and I tackle the cleanup. The bathtub is covered with plaster chunks and plaster-dust thickly lies over everything. I put the place completely right and it shines a dull, worn shine. The kitchen floor is hard work because there is so much stuff piled along the walls. One corner holds a couple sets of skis and ski boots. Another corner has a drafting table turned horizontal with kitchen items on it. It rocks back and forth when I shift the weight on the table by moving a few of the items around. It never fails to startle me and I reach out to steady it as if it were about to topple. Everywhere there are things to move and piles of dog hair. The green linoleum floor is black. I must pick up and move everything in order to sweep up the dog hair and loose dirt. Then I have to move everything again to mop. Woe, that wobbly table. While I am working, Cherry is in the bedroom continually talking on two phones; she talks about the other party’s astrology and romance problems. It takes me three hours to finish and I expect another hour of work because of the agency’s four-hour minimum but instead Cherry starts to pay me off. After she tells me how really clean everything looks, I ask with some hesitation if she knows about the four-hour minimum. Cherry informs me that the agency quoted a three-hour minimum. “And so the recession has finally hit the cleaning market!” I think to myself. There must be more people cleaning now so the agency must reduce the minimum in order to attract more jobs. Cherry takes my phone number and I leave feeling somewhat flat.

Cherry calls me up soon and this time I clean the entire apartment. There are four rooms counting the hallway and the bathroom as one. The front room has tall windows that open onto the street, a fireplace, and wood parquet floors that run back into the bedroom. The windows are landscaped with plants that hang down or sit on trunks before each windowsill. There are two bright blue movie-theater seats tottering, detached from the sturdy look of rows. The bedroom can be shut off from the front room by sliding wooden doors; a large bed, a small easy chair, and a lamp with a framed Roman engraving hanging above it on the wall, and various suitcases fill the dark room. I work hard for five hours and the place never really gets clean, but my impact alone makes a world of difference. Cherry goes out and asks me to answer the phone. When the phone rings,

I need a pen to write down the message. I open a drawer and find a pen and next to the pen is some grass. I pocket a little for myself. From the variety of clothes and underwear lying about I begin to gather that a man seems to be living here besides Cherry and her dog and cat, Orchards and Turtles, respectively. Cherry sometimes mentions a Jack. I feel exhausted down to my cells and Cherry gives me a generous tip. The grass turns out to be excellent.

Cherry says, “It is hard to get someone who really cleans.” I am asked to become a regular on Thursdays. I meet Jack Gleason who lives with Cherry, and I become an official member of the household. I have a question like, “Any bags for garbage?” and I walk up the hallway to the front room to find Cherry. The door is open and Cherry is doing a yoga exercise on a mat in the middle of the floor. She is wearing blue trunks and is holding a position in which she rests on her shoulder blades with one foot down in back of her head and the other sticking straight up in the air. I’m looking straight under her trunks at her black full crotch. Surprised out of my question, I turn quickly and resolve to ask later.

Cherry teaches yoga classes and does her own routine every day. Most often she shuts the doors and/or wears leotards or tights. Both Cherry and Jack are phone people. Cherry spends a whole morning relaying all of her friends’ and Jack’s business friends’ astrological highs and lows for the upcoming weeks. Cherry is the oldest of nine children, which she says explains her abhorrence of housework. She grew up in the Sonora Desert and pronounces “Malard” in a French manner. She is a vegetarian and so too are Orchards and Turtles. Cherry tells me about disasters to befall New York City. In 1980, there will be a great food and water shortage which will be ended by an earthquake that will split Manhattan in two and leave most of it under water.

Every week Cherry’s apartment is equally and totally dirty. Cherry comes more and more to rely on my coming and there comes to be more and more for me to do. The first thing to do is an hour’s worth of dishes. Cherry leaves the entire week’s dishes piled in the sink. She doesn’t even scrape the food off. There are at least four dirty pots sitting on the stove. Before I can wash the dishes, I must take all the dishes out of the sink in order to clear the drain. Cherry uses the kitchen sink as if it were a garbage can. The bottom of the sink holds three large handfuls of old, gloppy food. After the dishes are done, I wash down the stove and refrigerator. Next I clean the fixtures in the washroom. The bathtub once had been painted, so now every time I wipe it out, paint chips fall off. Paint chips are a nuisance to pick up when your hands are wet; often they will jam up under the fingernails. I sweep out the bathroom, hallway, and kitchen. There is always a lot of dog hair and kitty litter strewn about. I mop the floors with a string mop, which I wring out by hand. The water in the bucket turns jet black after each room. I dust the front room and bedroom. I sweep those two rooms out, moving about the arrangement of heavy, awkward furniture. Then I do likewise but this time with a mop and bucket. I run upstairs and knock on the door: “Hello, can I borrow the vacuum cleaner?” Then I bring the vacuum down on the rug in the front room. Done! Thursday is a heavy day’s work, but Cherry and Jack are not cheap in paying or tipping. Cherry gives me food to take home and expensive, unwanted clothes and shoes. Sometimes I snitch a little grass or household items like trash bags or saddle soap. I really feel shame at Christmas; Cherry gives me a generous amount of dope as a present and I have already a present pocketed.

Jack is an affable, slender young man with a moustache. He is from a very wealthy family in Trenton. He’s used to having servants around and relates to me with the perfect candor of somehow having grown up with me. Jack makes money by being a food broker. Occasionally he and Cherry fly to South America to raise the price of sugar. Jack confides to me that in a single afternoon he may easily make as much as $40,000. He and Orchards play around the house or go out running together. Jack’s real love is playing backgammon.

Cherry knows that I know my job and lets me do it all around her. I meet her girlfriends, hear her gossip, we talk about romance, I meet her backdoor friend. I put the cap back on her toothpaste. I confide bits of my heart to Cherry. We just talk about it. The household is run on a steady flow of hard cash. All the food is the most expensive health brands and there are five-gallon water bottles for drinking and in case of drought. What is really needed is a live-in maid with her own budget. If I were she, I would buy a big garbage pail with big trash bags and I would buy a vacuum cleaner to really get all the hair and dust off the floors. Cherry once refers to me as the “maid” as she talks over the phone. Being described as the maid at first hurts my feelings because I see my job as more independent and more of a service than maid’s work. But the work is like maid’s work. I finally realize that there is no definition of the word “maid” that does not include the word “woman” or “girl.” I don’t feel like a woman while I’m working. I do feel like yelling, “Cleaning Man!” at Cherry. But she is only talking into the telephone and maid is meant to mean something to the other party, not to me. Jack tells me that when the place is really filthy, he dreams of me. Jack with his aristocratic leniency has no need to call me anything other than my name.

I am cleaning in the washroom. I am about to wipe down a white ledge that I always wipe down. I’m moving off the items always found on that ledge. Here is something strange. A piece of a nylon stocking is wrapped tightly around something the size of a golf ball. I pick it up and notice that it is slightly mushy. I sniff it. My head almost recoils into the bathroom mirror as I flip the thing back onto the shelf. I have never smelt anything like that before! What can it be? My first thought is that it is an occult little bag filled with human excretions and fingernails. I don’t touch it again. Later as I’m putting on my shirt to go home, I overhear Cherry and Jack talking in the front room.

“I think Bob found my [unintelligible] in the washroom today!” Cherry says.

“Wow!” Jack exclaims, “Girl, you really have no class!” They both break into hysterical laughter. I step into the room and they dummy up. The next week while I’m cleaning the washroom, I notice something hanging from the shower nozzle high up the wall. It must be the same thing but it has grown! This time it appears to be a child’s foot dangling in a stocking. I let it be. Explanations are offered by my friends. It’s shit. It’s witchcraft. It’s menstruation flow. It’s cheese. I don’t know. I’ll never know.

One day I come to work stoned. There is quite a pile of dishes as usual. What is unusual is that Cherry is not doing her yoga. Instead, she is lounging on her bed in her bathrobe. As is my custom, I centralize all the items to be washed by placing them on the tottering drafting table, which is directly behind me as I stand at the sink. Next to me, on my right, is the door to the bedroom. Every time I turn around to get a few more dishes to wash, I peek over to Cherry who is lying on her bed absorbed in a magazine. About the third time I glance at her, I start to feel a nervous excitation. Her blue bathrobe seems to be riding up her legs. I start taking fewer dishes at a time in order to secure more looks. I’m so stoned that I’m starting to feel dizzy. Each time I look, Cherry is in a new position. One time, she is lying on her back and her thighs are spread open on the bed. The next time, she is on her stomach lying across the bed so I can see the back of her legs up to the rise of her ass under the bathrobe. I am the slave in the kitchen, chained to the dishes as my mistress excites me. I flashback on the story of Spartacus and Clodia I read as a kid in the Olympia Reader. The slave turns around and looks over. The mistress’s head is carefully bent away. She sits over the side of the bed. Her bathrobe is loose and open in front. One beautiful breast hangs out. It gracefully slopes down and comes to a point. She is a statue of milk and marble. I reel around, the blood pounding vertically through my body in single giant spurts. The kitchen walls start to spin around me and go dark. I grab the kitchen sink and hold fast as I almost faint. The next time I have the strength to look, she is no longer there.

I, the good slave, never approach Cherry. Th

ere is so much potential, but as long as I stay a slave, nothing will really happen. Perhaps that is what both of our fantasies are about. I slave for Cherry but when I am done, I am free and independent. Cherry depends on me to clean up and make things livable. Our unspoken relationship works on work and then works itself out. In early spring, Jack and Cherry move out of the city to breathe the country air. I’ve lost my best customers but a good customer will always have reason to come back to New York City.

CHAPTER 3

Organization of Tasks

Tasks must get done. Knowing the most efficient order in which to do them is as important as knowing how to execute each individual task. You can’t do everything at once, so common sense tells you to chose one task and to begin.

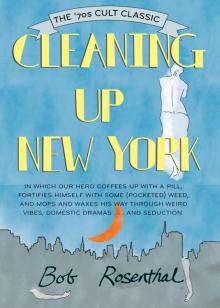

Cleaning Up New York

Cleaning Up New York